It was with the English Royal Guard that he began Empire, an extensive series that took the photographer on a three-year journey through 16 countries and principalities in Europe to meet 31 regiments. The Royal Horse Guards, Queen’s Life Guards and Grenadiers were quickly followed by the major figures of the Danish and Swedish guards, then the Norwegian, Scottish, Belgian, Dutch, French, princely (Monaco), Austrian, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, Vatican, San Marino and Greek guards. The undertaking was not exclusively photographic. Before the image, there is negotiation, then acceptance. Previously, the Rikishi series, produced in Japan in sumo wrestling circles, had given rise to similar manoeuvres. These negotiations and what follows, the photographer’s entry into a closed circle, are as important to the raison d’être of the project as the resulting image. The project has raised its standards, demanding more than simply pushing open the door of a school or ice rink, more than talking to a headmaster or coach. To stand there in front of the Scottish Black Watch or the Swiss Guards at the Vatican, he had to be accepted by the highest authorities, to cross the threshold of a royal castle and the Holy of Holies.

The individual’s desire to belong to a group, from the soldier to his regiment, meets that of the photographer towards the community he has chosen as his subject: to put an end to the peripheral position of the recorder, always confined outside the perimeter, be it a swimming pool, an ice rink or a wrestling ring. Empire thus marks a major turning point in the photographer’s artistic approach. To the 16 countries visited and 31 regiments listed, he adds, just after Greece in his book, the region of ‘Fréger’, where he presents his guard. He has everything: uniform, coat of arms, motto. The costume is serious, made with the advice and supervision of professionals. He will wear it on numerous occasions, with an alter ego, during performances (see the video on this subject). Wearing this uniform is a way of telling his models that he too is proud to face up to and willing to embody: embody his protocol, his desire for photography.

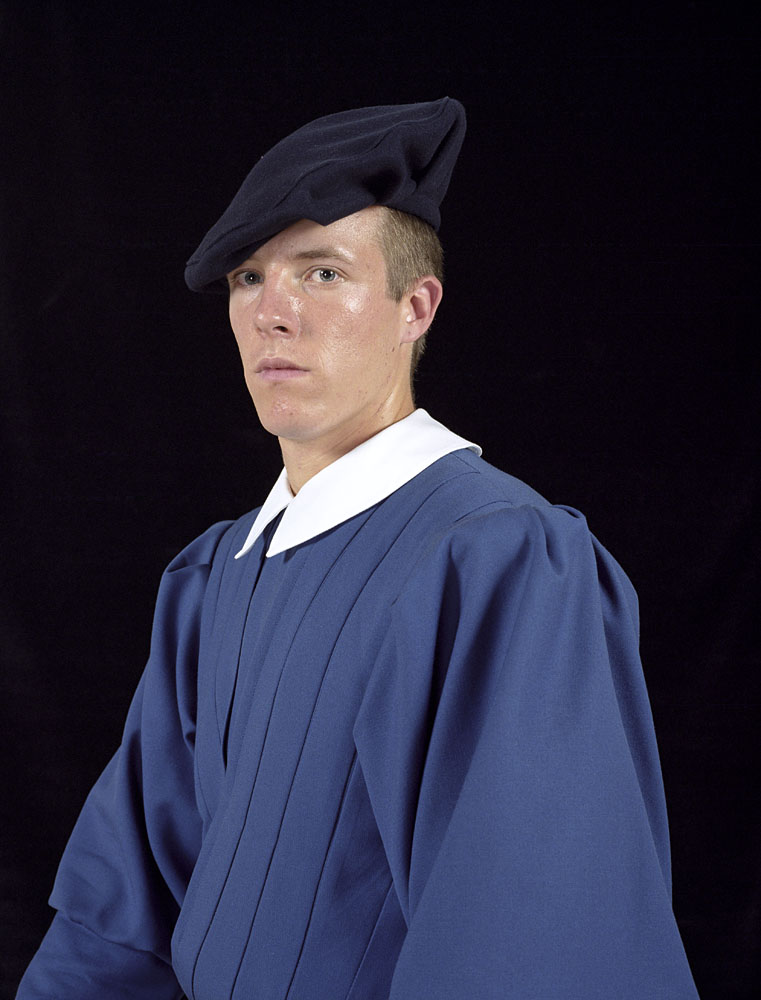

Empire favours bust portraits over full-length ones, approaching the clothing and its details with the same enthusiasm as the man in uniform. The photographer does not collect toy soldiers. If the poses are very posed and hieratic, it is because they respect the solemnity of the occasion, and if the view from behind is included for the first time, obscuring identity, it is to reveal the hidden side of those whose role is to defend and protect. The motif of putting on or adjusting the uniform, already used in previous series, is repeated, as if to emphasise the pride of slipping into this fur or woollen-trimmed skin and embodying it. Often, the soldier poses in front of a painting depicting battle scenes and military exploits: creating an image in front of another image and giving substance to mythology.

Empire finally evokes another community, that of Europe, as a territory sharing a common history and culture, suggested by the photograph at the very end of the series of the monument to Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, whose assassination on 28 June 1914 in Sarajevo precipitated the outbreak of the First World War. The photographer records the relics of this European empire. Bearskin hats, nickel-plated buttons and starched collars, uniforms that have sometimes remained unchanged for centuries, appear as good as new, inflated as they are by the desire to believe of the man who wears them.