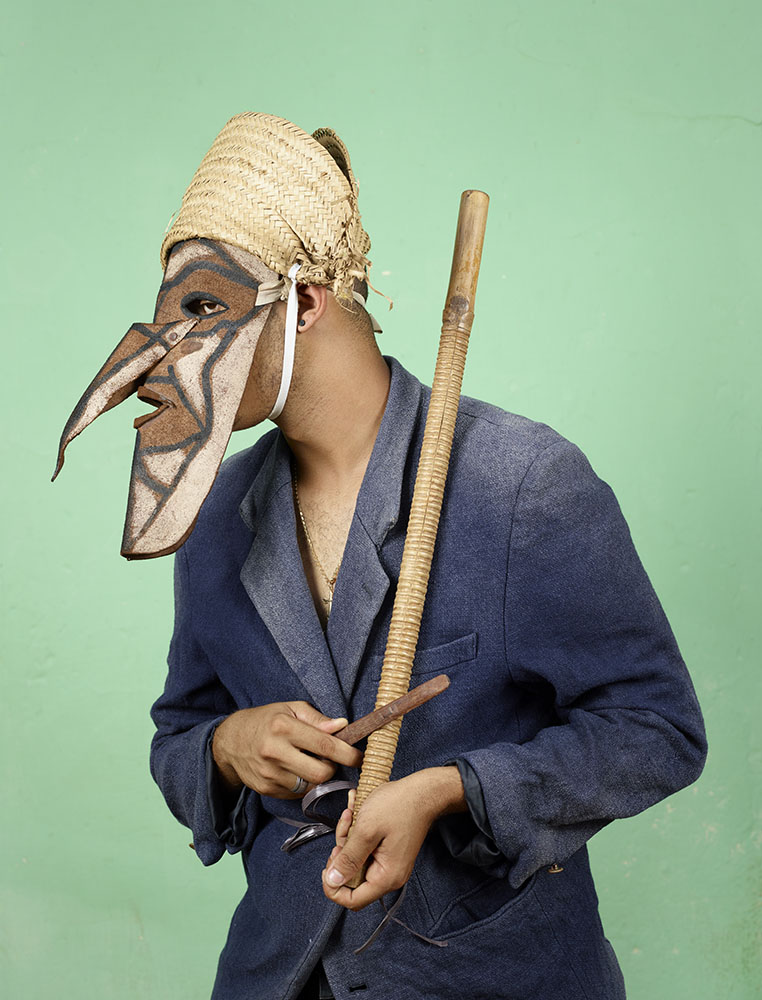

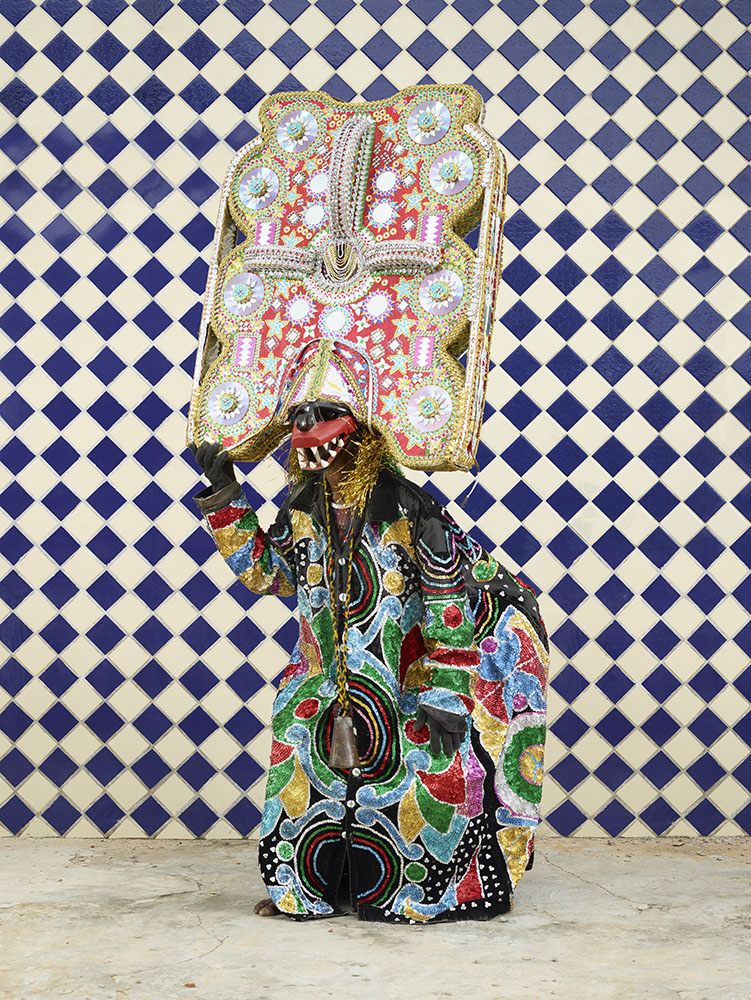

Cimarron is the third part of a photographic series begun in 2010 by Charles Fréger and dedicated to masquerades; after Wilder Mann (2010-), dedicated to the European continent, and Yokainoshima (2013-2015), located on the Japanese archipelago, Cimarron (2014-2018) is anchored in the territories of the Americas. In a geographical space stretching from the southern United States to Brazil and including fourteen countries, Charles Fréger this time draws up a non-exhaustive inventory of masquerades practiced mainly by the descendants of African slaves, celebrating the memory of their peers and their singular cultures.

“Cimarron”: the term used in the series initially designates the runaway slave in the Hispanic colonial world, then gives rise to the term “maroon”, evoking the heroic figure of the man resisting oppression after 1848, the date of the abolition of slavery. Behind the multitude of masked traditions presented, move the ghosts of men and women aspiring to freedom.

Through this corpus, masquerades unfold from one to the other in which, between masks, make-up, costumes, ornaments and accessories, African, indigenous and colonial cultures intermingle, caught up in the vertigo of a centuries-old syncretic movement. The masquerade is more than ever here a territory of setting in regard of a community by another, a space where we replay, where we reinvent the relation to the oppressor either to mimic it, or to reverse it, always to subvert it.

Extracted on purpose from the tumult of the carnival or festival to which they belong, the figures embodied by the masquerades take place, monumental and hieratic, in an environment chosen by the photographer for its pictorial qualities. He focuses his attention on the aesthetic verve expressed by these silhouettes as well as on that concealed in the urban or rural environment. A pink truck tarpaulin soiled with soot becomes the backdrop for the Pintao in the Dominican Republic; a carpet of tall grass greets the colorful plumage of the Caboclo de Pena in Brazil. Colors and materials resonate with those worn by the silhouette, amplifying, like a stage set, the outrageousness, beauty, otherness and animality embodied by the masquerade. Charles Fréger moves the silhouettes as if to better make the singular voice of these theatrical bodies heard, each one replaying with its own language the acts of a history made of domination, suffering and resistance. On the road to Cimarron, the extent of which only partially expresses the practice of slavery, the forms of a counter-power are deployed, which the masquerade, far from concealing, comes to liberate.