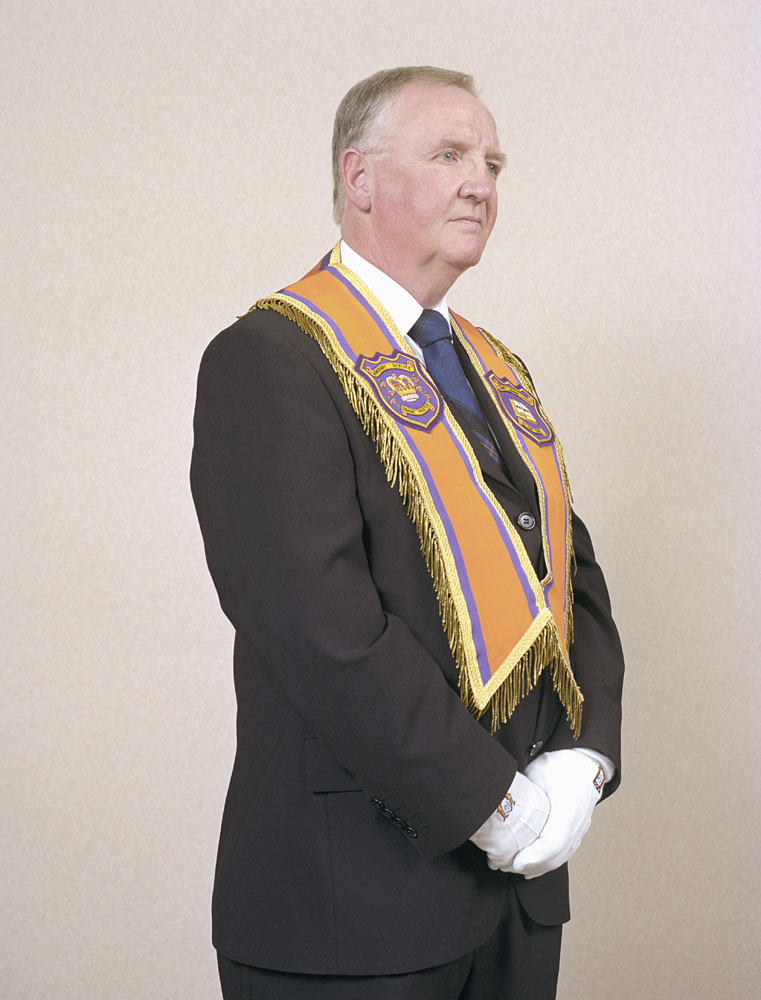

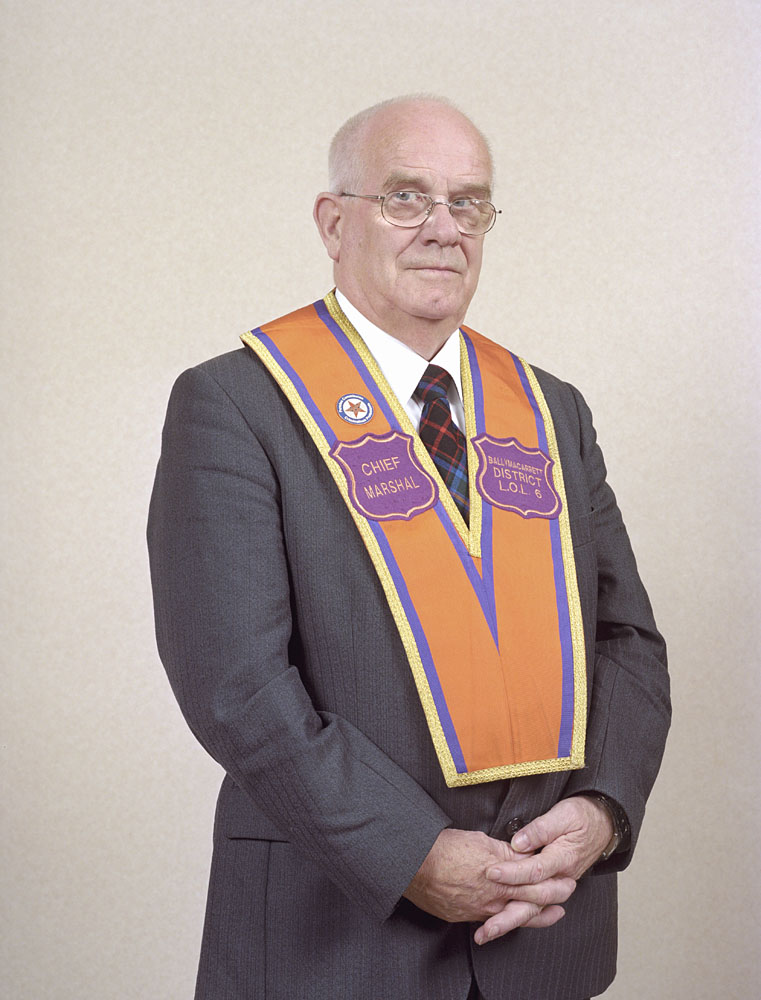

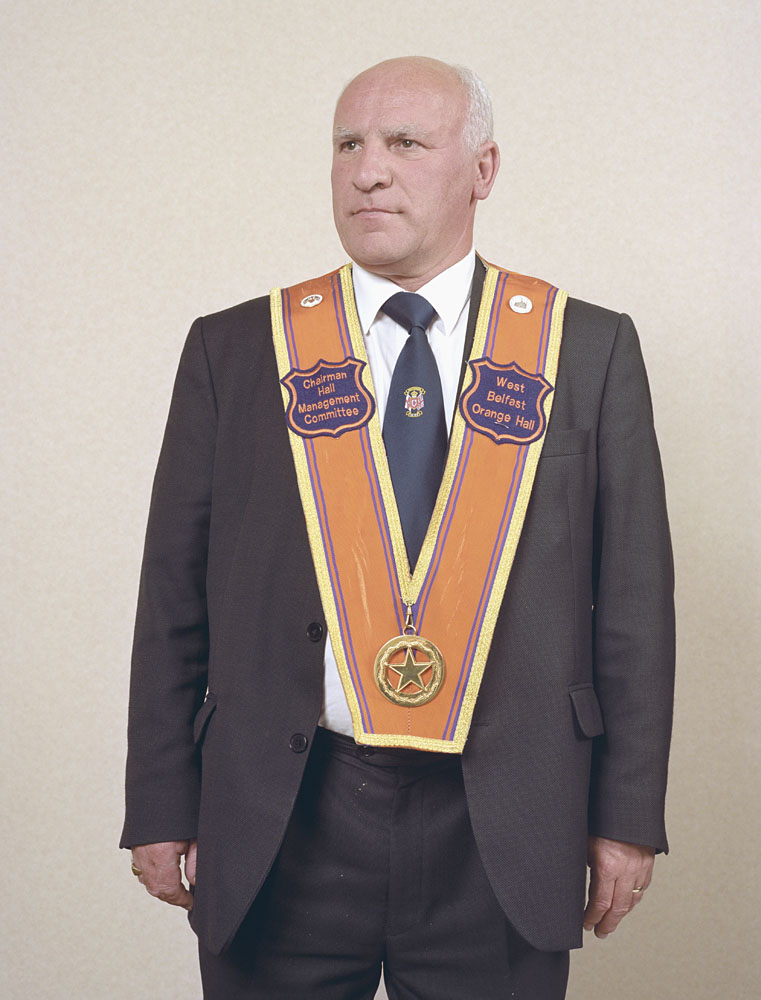

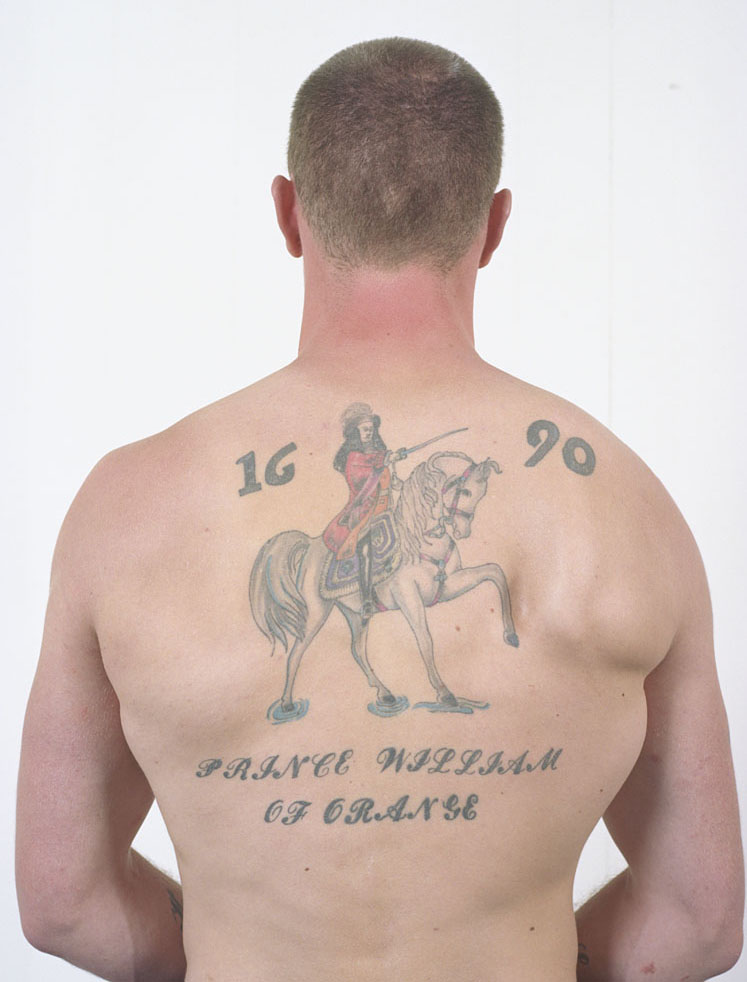

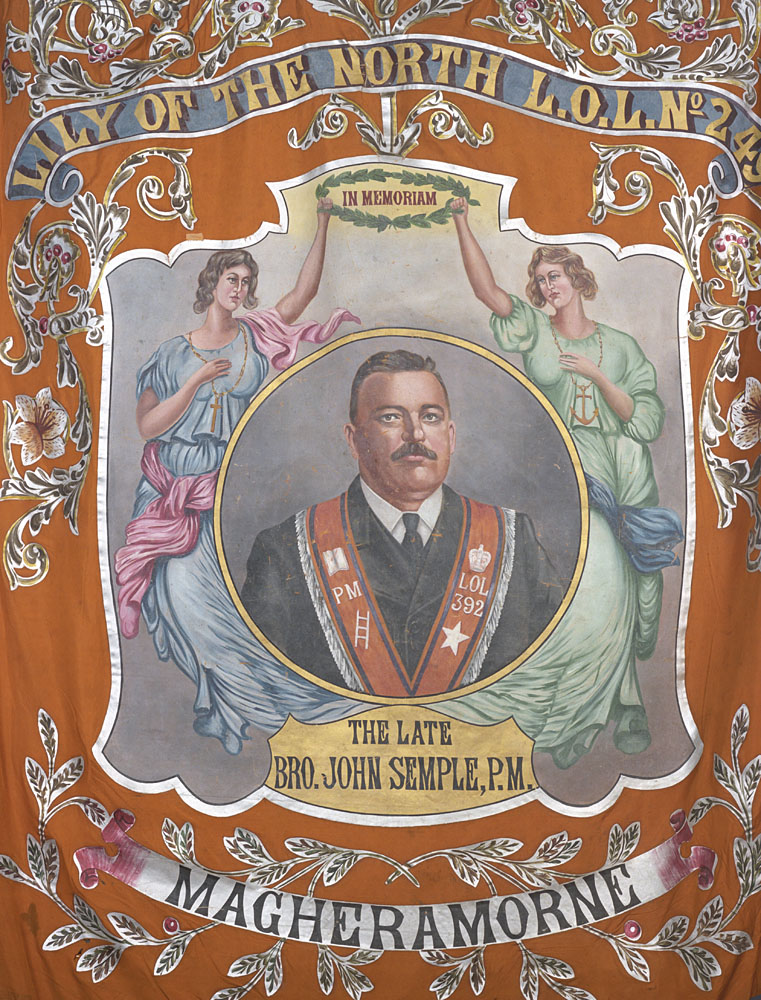

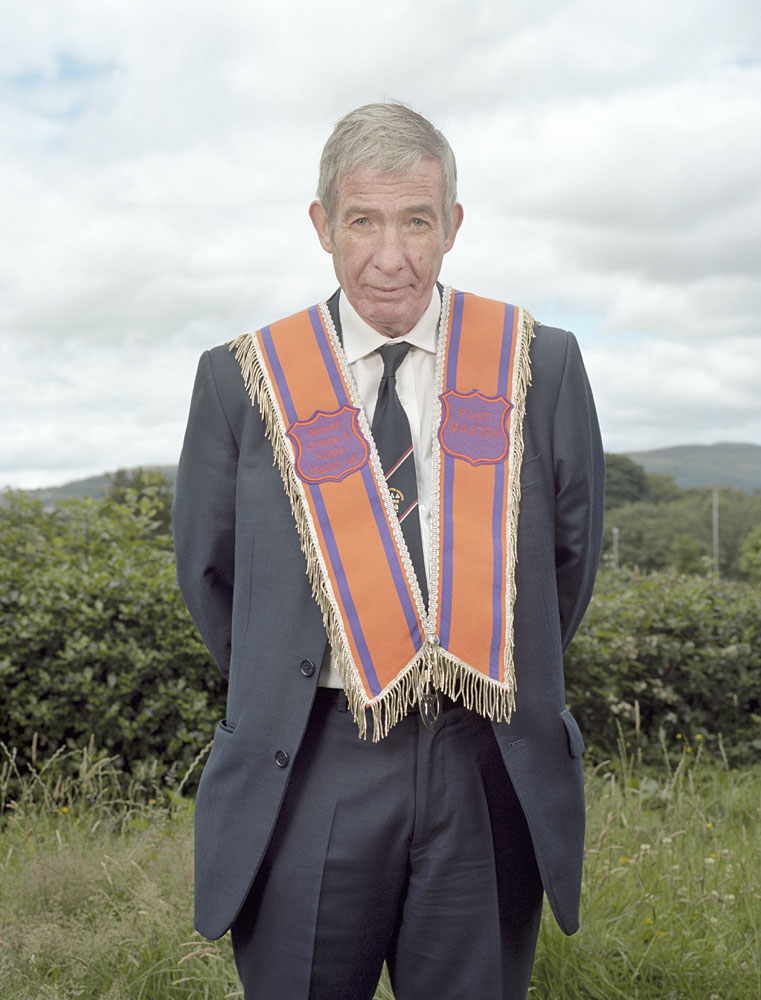

Men in suits and ties, wearing bowler hats, carrying swords, their torsos still bulging behind an orange scarf: these are the Orangemen, members of the Orange Order. Protestant brotherhood of Northern Ireland, the Orange Order is organized in lodges. Two of them granted Charles Fréger permission to photograph them: The Lodge and The Field. For the first, he chose to make his portraits within the lodge, focusing on the lodge masters. Their black silhouettes stand out against a pale wall; there is no indication across the image as to the nature of the place, other than these photographs of paintings that punctuate the portraits. Between two orangemen, we observe the irruption of a clergyman, sacred book in hand. This painting, with its brown surface and cracks, is followed by another painted image, more naive in style, taken from the banners carried in processions. It presents a rider, who will be found later, he appears on his mount, sword in hand, crossing a river. Here is the hero: William of Orange or William III of England, Prince of Orange, fierce opponent of the right of Catholics and their emancipation, as well as the possibility of the country’s independence from the Crown of England. As a counterpoint to the neutrality of these early portraits, those of The Field Lodge were painted on the occasion of the annual July 12 procession, infamous for the many clashes between Protestants and Catholics that accompany it at regular intervals. The parade commemorates the Battle of the Boyne, won in 1693 by William of Orange against James II, supported by Louis XIV, who had left to regain the throne of England. Here, the green of the wet countryside is everywhere, the outfits always black, white and orange and the lawns mowed short. This is where they finish their procession, ending it with a picnic. There are other close-ups of banners and their heroic figures. The photographer here, as in his previous series Merisotakoulu devoted to the Finnish navy, puts in abyme the representation of the chosen group by integrating the iconography of the brotherhood within his corpus of images. For here, the “making of the body” goes beyond the uniform, through the cult of the image of the hero, found in several instances, on walls, banners but also on the bodies, in the form of tattoos.